By Rébecca Franco, Euromix PhD Researcher, 15 April 2019

Since the 1990s, ‘métissage’ [mixture] is often used in French public and political discourse as the ultimate end and means of the post-racial dream.1 Métissage is a specifically French concept that is invoked to talk about the cultural and ‘ethnic’/‘racial’ mixing that is indicative of the integration of different (non-white) groups in the French national identity. At the same time, however, the French political and social dialogue is filled with concerns about the descendants of (post)colonial migrants, especially about the residents living in the marginalised suburbs known as the ‘banlieues’. These citizens have made political claims to redress racialized inequality. However, they have faced rejection by the government based on the argument that this reinforces particularistic notions of identity, which is in the French tradition of universal Republicanism seen as ‘unfrench’.

So what is going on here? In the country of ‘liberté, egalité et fraternité’, everyone is supposed to be equal. So, racialized inequality is not seen as a valid basis of political claim-making. And yet, the descendants of the people whose labour and resources helped build the country are marginalised on the basis of racialized logics. Freedom is circumscribed, equality differentiated, and brotherhood conditional.

In this blog, I will go into the difficulties of understanding and talking about the role of ‘race’ and processes of racialisation in France. Through this, I explain and motivate my research on the regulation of ‘mixture’ at a time in which many (post)colonial immigrants moved into France.

The banlieue

Let us first turn to the current situation of the descendants of postcolonial immigrants in France so to comprehend what is at stake. According to the decolonial intellectual Mbembe, the French state has refused to address the issue of ‘race’, while simultaneously engaging in practices of racialisation at multiple levels of society.2 This becomes apparent in the issues surrounding the ‘banlieues’. The French marginalised suburbs are heavily populated by French citizens of African descent: some first generation, but many residents have been in France for multiple generations. The ‘banlieusard’ [the residents of the banlieue] is seen as ‘savage’ in the same way as was done in the colonies.3 They are often cast aside as threats to the nation, as foreigners – although they are French citizens.

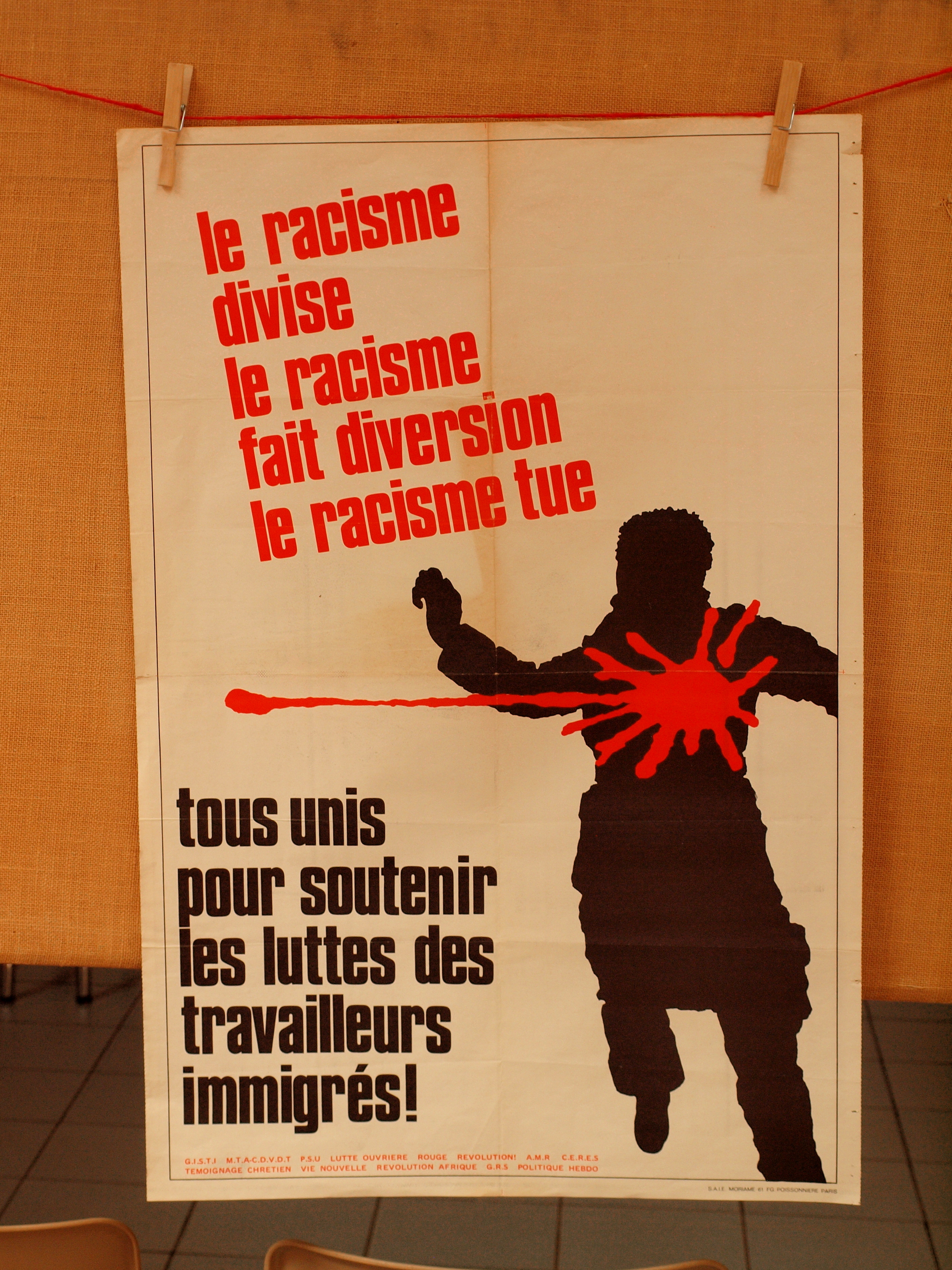

The residents of these urban zones have challenged amongst others racism, spatial marginality, racialized police brutality, and lack of opportunities,4 as they fight for a place in postcolonial France.5 Fed up with the marginalisation their (grand-)parents have had to deal with, they struggle for recognition, dignity, and equality.

On the side of the state and ‘mainstream’ media, however, the banlieues are represented and discussed as a hotbed of crime, despair, and unrest. The problems in the banlieues are more often discussed as proxy of the problem of ‘immigrants’ than to address issues of residents. Accordingly, the urban zones are problematized as threats to national security, and policies have mostly revolved around repression rather than solutions.6 In response to the formations of group identities, government is concerned with what they call ‘communautarisme’ [pejorative term for ‘segregation’ based on group identity], as the residents are accused of refusing to integrate.7

Negating ‘race’

The French authorities and politicians often use this rejection of communautarisme as an argument to negate the particular experiences of marginalisation based on markers of identification, such as ‘race’ or ‘ethnicity’. Whereas the term only really gained currency in the 1990s – as the ‘dangerous’ alternative to métissage – it is today vilified for testifying as the rejection of French universalism. In this same vein, ‘race’ or ‘ethnicity’ is not a legal category nor included in the census in France. The argument is based in the French Republican idea that universalism and equality are the integral tenants of French society.8

In an op-ed in response to the referendum in Switzerland on the banning of minarets in the newspaper ‘Le Monde’, the then-president Sarkozy asserted: ‘National identity is the antidote to tribalism and communautarisme. […] Métissage is the willingness to live together. Communautarisme is the choice to live separately.’9 Whereas communautarisme is rejected, métissage is promoted as proof of French universalism. Through this, métissage indicates tolerance (on the side of the state/French society), while communautarisme indicates intolerance (on the side of the ‘other’). In both concepts, however, the historical dynamics of power, are negated, and so through this discourse the French state becomes absolved of responsibility.

The rejection of specific markers of identification, such as race, as a category of analysis, solidarity and political claim-making, then, becomes hazardous if we consider the ways in which they have played an essential role in the making of modern France. Accordingly, the politics of ‘colour-blindness’ has been criticized for negating the historical, institutional, and structural inequalities based on such markers of identification.10

So, how can we try to understand the processes of racialisation in the French context?

Researching race and mixture

The difficulties in understanding and researching racialisation in general, and France in particular, lies in the flexibility of the concept of ‘race’ itself. Stuart Hall has argued how ‘race’ is a floating signifier, as it has disparate meanings that can be activated in specific contexts. Similarly, ‘race’ can operate under covert signifiers that invoke ideas of race without enunciating them. Covert racialisation is not limited to the French context by any means. However, the French context in which the official narrative of France is that is has never ‘done’ race because of its investment in universalism, makes it ever the more important to consider the flexibility of race.

Critics of the French narrative of their exceptional equality and universalism have argued that ‘inassimilability’ was used as a covert for exclusion on ‘racial’ terms. This played a role under colonialism: subjects could in theory become citizens, if they were ‘evolved’ enough, spoke perfect French, and acted like ‘real Frenchmen’. In reality, this was close to impossible.11 In this way, difference is evaluated against the universality of France.

In other words: France is seen as universal perfection. Everybody is equal, except if you cannot adhere to that French perfection: then, you are ‘inassimilable’, different, unequal (and can be colonized).

In this light, the (renewed) interest in métissage as a marker of integration and the goal of post-raciality warrants a closer examination. In French, unlike the English terms ‘miscegenation’ and ‘hybridity’, the notion of métissage indicates both ‘racial’/’ethnic’ mixture as cultural meanings of mixture (unsurprisingly, given the historical connection between assimilability in cultural terms and racialized exclusion). Whereas mixed couples are seen as a measure of integration, the concept métissage itself does not explicitly talk about race as it is made devoid of its biological meaning in today’s context.

Still, the regulation of ‘mixture’ and mixed relationships have played a central role in the creation of identities and in ordering society along these identities. ‘Mixture’ presupposes the existence of two different parts. So, the way in which ‘mixture’ of people is regulated can help show how boundaries are created and enforced. The regulation of ‘mixture’ as a way to create and regulate the native and the foreign, white and non-white, colonizer and colonized, has a long history. Reading this history back into its contemporary use can help understand why and how the investment in color blindness negates the state’s responsibility in racialized regulation of belonging.

History of ‘mixture’

Several scholars have looked at the ways in which mixture was regulated at different moments in French history across the French colonial field. In colonial times, the authorities promoted ‘mixed’ relationships when it was seen as a practical solution to men’s desire, but it became mostly vilified when scientific racism became popular at end of the 19th century.12 ‘Mixed race’ children (metis) were seen by the authorities as unrooted and problematic, as the fear for a ‘monstrous metis’ as a rootless danger was perpetuated through art and literature. Interestingly, a decree in the 1930s for ‘metis’ in the colonies made ‘mixed race’ a condition to obtain French citizenship through that decree.13 This illustrates how the regulation of ‘mixture’ reveals the underlying racial logics of otherwise universalist jurisdiction (at least on paper). At the same time in the metropole, immigration was promoted only insofar as immigrants were deemed assimilable to the French in terms of having families with the French population.14

Just before independence in West Africa, Leopold Senghor, a Senegalese intellectual and later first president, used the concept of métissage to advocate for cultural hybridity as an alternative to nationalism. For multiple reasons that essentially revolved around the French government’s rejection of an equal federation with African states, the notion of métissage lost currency over the course of decolonization of West Africa.15

In France, research and discussion on ‘mixture’ only pops up again in the 1980s/1990s. These works and political discussions discuss the meaning of mixture in terms of integration of second-generation immigrants. Besides, the fear for ‘mariages blanc’ [white marriages, i.e. sham marriage for documents] made mixed (nationality) families and couples hypervisible.

Generally, regulatory practices and discourses depended on the specific ‘needs’ of the different authorities at that moment in time and space, which were not always cohesive. Tracing the histories of the regulation of ‘mixture’ shows a fragmented field of anxieties, regulations, and governmental practices that crafted, protected, and contested racialized categories and belonging. The discourse about métissage today, thus, is a continuation of the uncomfortable history, rather than a break from it.

There is, however, little literature and attention the regulation of ‘mixture’ in the period between WWII and the 1980s. During the 30 years of the trentes glorieuses (1945-1975), France underwent massive change. It transformed from an Empire to a modern European nation-state (although they still had and still have foreign territories). At the same time, many Northern Africans and Sub Saharan Africans moved into the French metropole, as they transformed from colonial subjects, to differentiated citizens, to postcolonial immigrants. Whereas this period is remembered as a time of open immigration, the regulation of immigration and belonging is more complex and fragmented. During this period, the postcolonial borders of contemporary France were crafted. Research into the regulation of mixture during this time can help understand how racialisation played a role. Accordingly, it can contribute to a more critical understanding of the contemporary discussion on métissage, communautarisme, and belonging of the descendants of postcolonial immigrants.

Conclusion

If today métissage is seen as an unproblematic solution, then political claims based on racialisation are rejected and the responsibility of the state is negated. Since talking about ‘race’ is seen as ‘unfrench’, and therefore explicit measures to tackle the issue of racism is seen as ‘unfrench’, then perhaps we need to open up the narrow way in which the role of ‘race’ and racialisation in French history today is remembered and understood.

Research on the historical regulation of ‘mixture’ is a fruitful line of inquiry because it can help reveal how the boundaries have been created, maintained and contested. Reading the history of the regulation of ‘mixture’ back in to today’s discussions can help understand the false dichotomy between métissage and communautarisme, as processes of racialisation become apparent.

- Whereas in my research, I favor the concept ‘interracialized intimacies’ to mixture, in this blog I use the term mixture because this is the term used in the archives. Interracialized intimacies indicates the process of racialization inherent in the designation of some intimacies as ‘mixed’.

- Mbembe, A. (2009). Figures of multiplicity: can France reinvent its identity? In C Tshimanga D. Gondola and P. Bloom eds. Frenchness and the African Diaspora: Identity and Uprising in Contemporary France, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Mbembe, A. (2005). La République et sa Bête : À propos des émeutes dans les banlieues de France. Africultures, 65(4), 176-181.

- Boubeker, A. (2013). The outskirts of politics: The struggles of the descendants of postcolonial immigration in France. French Cultural Studies, 24(2), 184–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957155813477797

- See for example the advocacy group ‘Les Indigenes de La Republique’ http://indigenes-republique.fr/

- Avenel, C. (2009). La construction du « problème des banlieues » entre ségrégation et stigmatisation. Journal français de psychiatrie, 34(3), 36-44. doi:10.3917/jfp.034.0036.

- Moran, M. (2017) Terrorism and the banlieues: the Charlie Hebdo attacks in context, Modern &Contemporary France, 25:3, 315-332, DOI: 10.1080/09639489.2017.1323199

- Léonard, M. des N. (2014). Census and Racial Categorization in France: Invisible Categories and Color-blind Politics. Humanity & Society, 38(1), 67–88.

- See https://www.lemonde.fr/a-la-une/article/2009/12/08/pour-le-chef-de-l-etat-l-identite-nationale-est-un-antidote-au-communautarisme-par-nicolas-sarkozy_1277587_3208.html

- For example, see Stovall, T. E., & Van, . A. G. (2003). French civilization and its discontents: Nationalism, colonialism, race. Lanham: Lexington Books. Peabody, S., & Stovall, T. E. (2003). The color of liberty: Histories of race in France. Durham: Duke University Press.

- For archival research on this in West Africa, see Coquery-Vidrovitch, C. (2001). Nationalité et citoyenneté en Afrique occidentale français: Originaires et citoyens dans le Sénégal colonial. The Journal of African History, 42(2), 285-305

- White, O. (1999). Children of the French Empire: Miscegenation and Colonial Society in French West Africa 1895-1960. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Saada, E. (2007). Les Enfants de la Colonie: Les metis de l’Empire francais entre sujéton et citoyenneté. Paris: La Découverte.

- Camiscioli, E. (2009). Reproducing the French Race: Immigration, Intimacy, and Embodiment in the Early Twentieth Century. London: Duke University Press.

- Cooper, F. (2014). Citizenship between Empire and Nation: Remaking France and French Africa, 1945-1960. Princeton University Press.