di Andrea Tarchi, Euromix ricercatore PhD, 17 luglio 2020

L’uccisione di George Floyd, avvenuta a Minneapolis il 25 maggio 2020 per mano della polizia, ha scatenato un’ondata di proteste transnazionali guidate dal movimento Black Lives Matter. Le proteste, che inizialmente hanno bersagliato i sistemi di disuguaglianza razziale e la brutalità della polizia inerenti agli Stati Uniti, hanno attraversato in poco tempo l’Atlantico e hanno trovato la loro articolazione nel contesto europeo. Mentre da un lato le proteste hanno affrontato principalmente le strutture di disuguaglianza razziale contemporanee che trovano le loro radici nella storia coloniale dell’Europa,dall’altro hanno anche preso di mira uno specifico campo simbolico. In particolare, si sono concentrate sulle statue che ancora valorizzano e celebrano quelle figure che hanno avuto un ruolo vitale nell’istituzione e nella proliferazione della tratta degli schiavi e delle economie coloniali. Non è la prima volta che questo tipo di statue vengono attaccate dai manifestanti – il caso più famoso è il movimento Rhodes Must Fall del 2015.1 La differenza è che ora le statue vengono veramente abbattute, come esemplificato dall’ormai famoso caso di la statua di Edward Colston a Bristol.2 Questa ondata di proteste contro i simboli del colonialismo e della schiavitù ha raggiunto anche l’Italia, colpendo in modo specifico la statua di un famoso giornalista italiano, Indro Montanelli, il quale ebbe un rapporto di concubinato con una minorenne eritrea durante l’invasione italiana in Etiopia del 1936. La storia di Montanelli, tanto quanto il dibattito sulla sua statua e le proteste che ha innescato, rappresentano uno spaccato estremamente esemplificativo della società italiana e del rapporto che ha tuttora con il suo passato coloniale. Alla luce della richiesta di giustizia razziale seguita all’uccisione di George Floyd, il dibattito pubblico italiano sulla statua di Montanelli fa luce sulla mancanza di riflessioni sul passato coloniale italiano e sugli effetti che ancora ha sul suo sistema contemporaneo di disuguaglianze.

Il concubinato coloniale: simbolo della violenza intersezionale del colonialismo

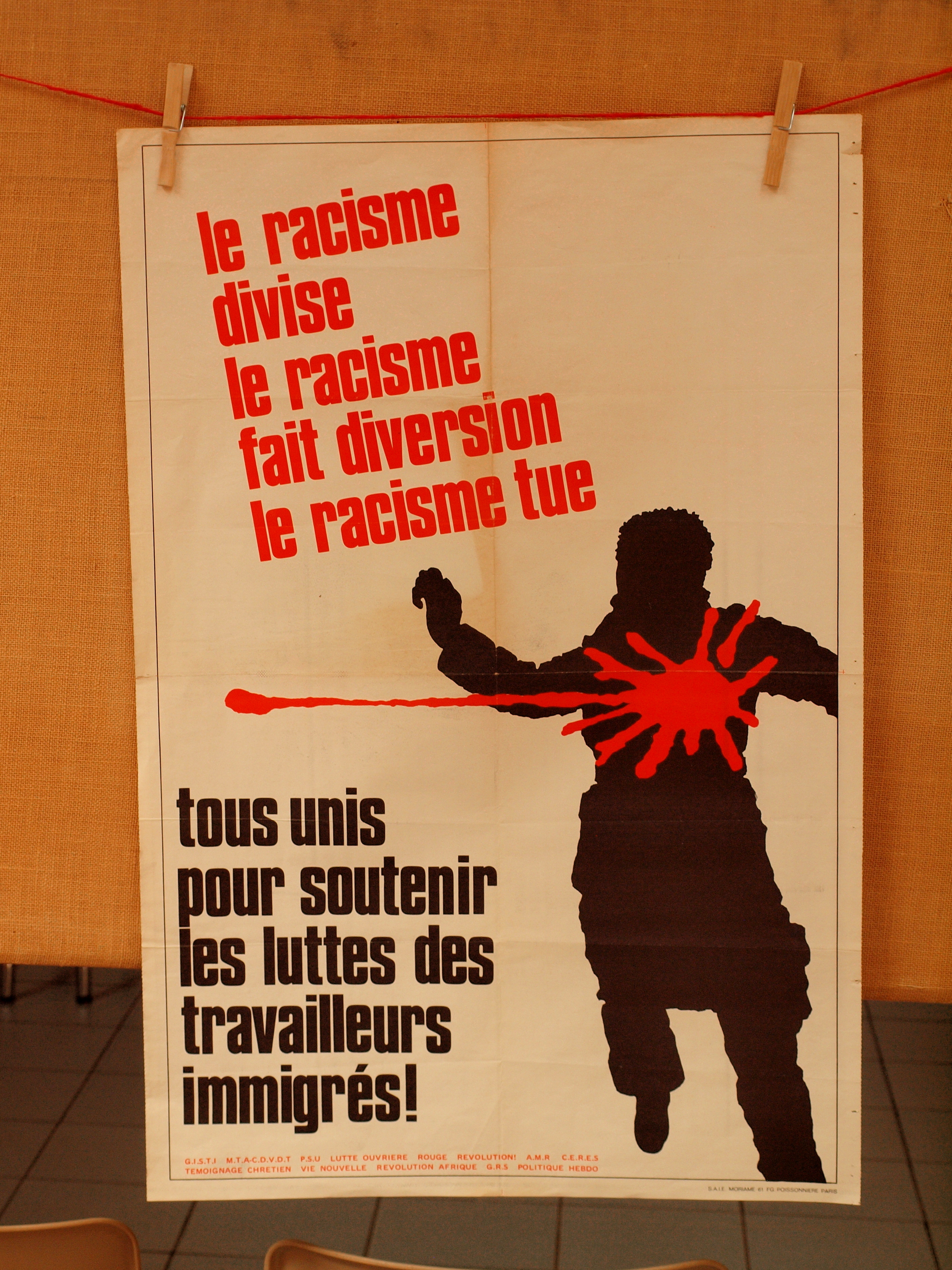

Durante l’espansione coloniale europea, gli ufficiali e i funzionari coloniali bianchi appartenenti alla borghesia spesso intrattenevano rapporti sessuali con donne razzializzate nelle colonie, in una pratica ampiamente sostenuta da secoli come mezzo per fornire agli uomini bianchi benestanti lontano da casa uno sbocco sessuale più dignitoso della prostituzione. Poiché la pratica era così esemplificativa delle relazioni di potere razziale, di genere e di classe insite nei contesti coloniali, era diffusa in tutte le colonie in momenti e continenti diversi. I casi di concubinato studiati nei contesti delle colonie spagnole (McKinley 2014), olandesi (Ming 1983, Stoler 2002) e inglesi (Ballhatchet 1980, Hyam 1986) sono solo alcuni esempi della ricerca che testimonia l’estrema diffusione della pratica. Le colonie italiane non fecero eccezione, come attestano le ricerche condotte da Sòrgoni (1998) e Barrera (2002) sulla specifica forma di concubinato tra ufficiali italiani e donne eritree conosciuta come madamato. Come per gli altri contesti coloniali, le relazioni miste di concubinato erano incoraggiate dagli amministratori coloniali italiani, i quali spesso spingevano gli ufficiali dell’esercito a prendere una donna locale come concubina come mezzo di conforto sessuale e domestico.

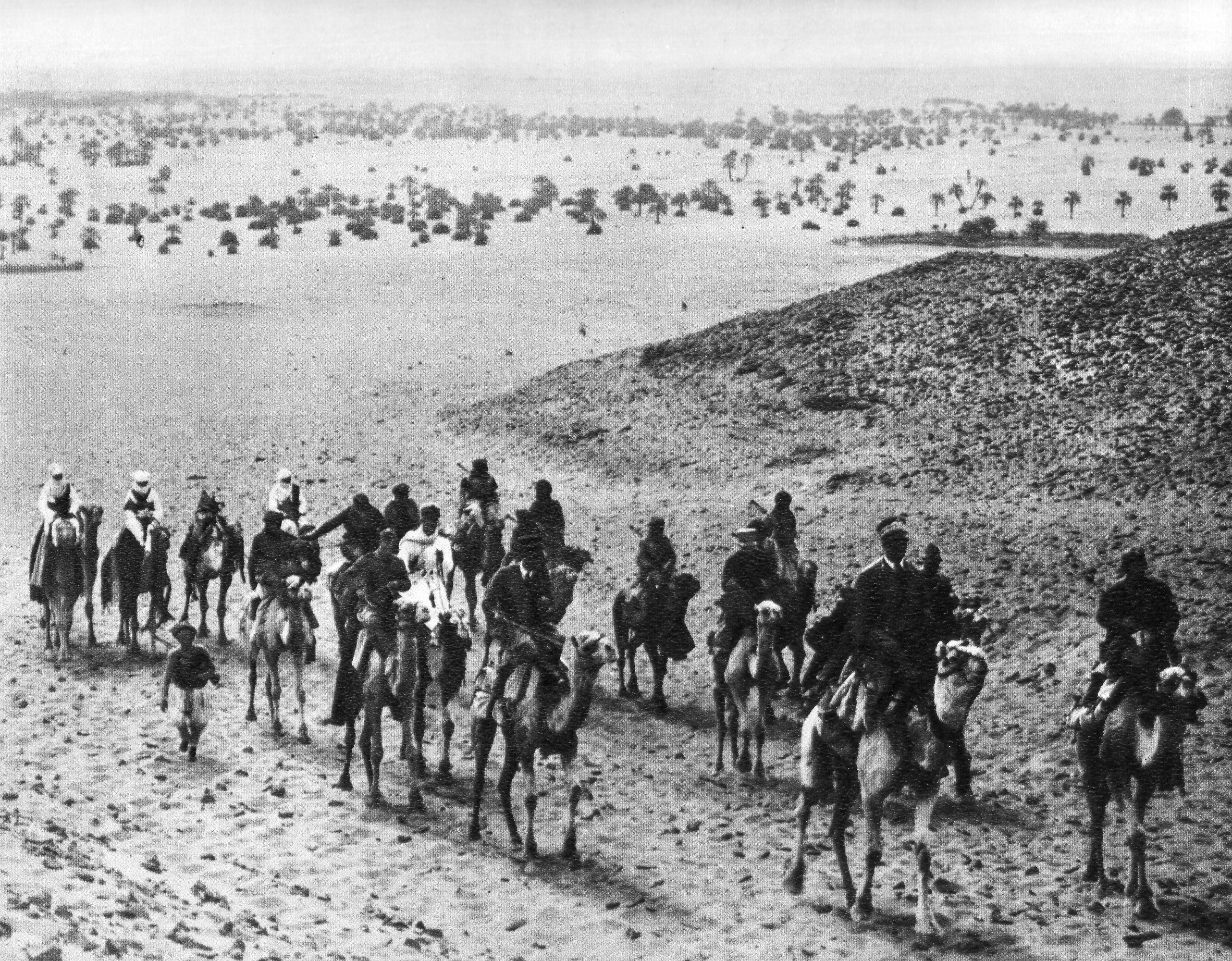

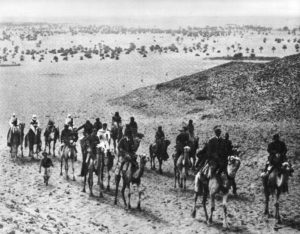

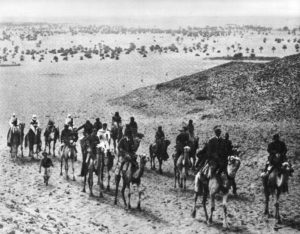

Uno di questi ufficiali schierati nell’Africa Orientale durante l’invasione italiana dell’Etiopia (1935-1937) fu Indro Montanelli, un ufficiale toscano che, come tutti sanno, in tempo divenne uno dei giornalisti più celebri della storia del giornalismo italiano. L’allora tenente di 24 anni fu incaricato dal suo superiore di “affittare”3 dai suoi genitori una bambina Bilena di 12 anni di nome Fatima (ma ribattezzata dallo stesso Montanelli Destà) come concubina. Dopo essere diventato famoso nell’Italia repubblicana post-fascista, Montanelli ha ricordato la sua concubina in più occasioni senza rinnegare il suo comportamento di colonizzatore maschio bianco nei confronti della sua concubina razzializzata. In un’occasione, quando gli fu chiesto da un conduttore televisivo, si vantò in termini sprezzanti di “aver scelto bene”,4 mentre nella sua colonna nel Corriere anni dopo descrisse i suoi critici come ” imbecilli, ignari che nei Paesi tropicali a quattordici anni una donna è già donna, e passati i venti è una vecchia.”5 Non sorprende che queste dichiarazioni abbiano provocato critiche da parte di attivisti e intellettuali, con l’evento ampiamente considerato nel discorso mediatico italiano come una macchia nella carriera di un uomo brillante. Questa macchia, tuttavia, non impedì al comune di Milano di erigere una statua in suo onore nel centro storico della città nel 2002, un anno dopo la morte del giornalista.

Com’era prevedibile, la statua ha suscitato molte critiche da parte di varie associazioni femministe, LGBT+, e anti-razziste nel corso degli anni, visto la natura impenintente con cui il giornalista continuò a ricordare le sue relazioni sessuali con la bambina eritrea. Tali critiche sono riemerse bruscamente il 13 giugno 2020, a seguito delle proteste mondiali innescate dall’uccisione di George Floyd. La statua è stata “vandalizzata”: alla sua base, un gruppo di studenti che ha rivendicato l’azione, ha scritto “razzista, stupratore”, e l’ha coperta di vernice rossa. In un video successivamente pubblicato dagli studenti, è stato richiesto l’abbattimento definitivo della statua.6 I manifestanti hanno identificato la statua di Montanelli come il simbolo della celebrazione di un individuo che esercitò senza patemi d’animo un’estrema violenza sessuale coloniale su di un bambina. Come per le statue a Bristol e negli Stati Uniti, agli occhi dei manifestanti la statua di Montanelli rappresenta un chiaro simbolo dei lasciti razzisti e patriarcali del colonialismo.

Perche e’ ancora importante: il dibattito pubblico italiano sulla memoria del colonialismo

L’azione degli attivisti ha suscitato un dibattito mediatico sul valore della statua e dello stesso giornalista. I difensori dei valori dell’uomo celebrato dalla statua basano principalmente la sua apologia su di una vecchia argomentazione che i ricercatori del colonialismo italiano conoscono molto bene. Tale argomento ruota attorno alla minimizzazione del legame che lega la società italiana contemporanea al suo passato coloniale. In questo caso, la declinazione di questa argomentazione si basa sulla normalizzazione della pratica del concubinato durante il colonialismo, la quale, come detto, fu ampiamente incoraggiata dagli amministratori coloniali. In questo senso, Marco Travaglio, un influente giornalista contemporaneo, ha sostenuto che Montanelli era “un figlio del suo tempo” e che “giudicare i fenomeni storici con gli occhi di qualche decennio dopo non ha alcun senso.”7 Un altro editorialista di prim’ordine come Beppe Severgnini è intervenuto per sottolineare come “quella vicenda — non esemplare, certo — non rappresenta l’uomo, il giornalista, le cose in cui ha creduto e per cui s’è battuto”.8 La protesta degli studenti milanesi è stata di breve durata e non ha mai raggiunto la massa critica richiesta per far rimuovere la statua. Allo stesso modo, il dibattito pubblico sul valore della statua e sul suo significato storico per la nostra società è scomparso nel giro di poche settimane. Tuttavia, sia la protesta che il dibattito che ha innescato mettono in luce la sconnessione ancora rilevante tra il passato coloniale italiano e la nostra società contemporanea.

Da un lato, la protesta in sé è esemplificativa della qualità del discorso pubblico italiano sul suo passato coloniale e presente postcoloniale. L’obiettivo della furia iconoclasta degli attivisti italiani non è stato quello che ci si sarebbe potuti aspettare: figure come Benito Mussolini, per la sua politica coloniale e imperiale e l’emissione di leggi razziali, o anche figure del partito fascista come il criminale di guerra Rodolfo Graziani , l’architetto dell’omicidio di massa di decine di migliaia di libici ed etiopi (Del Boca, 2005), non sono state toccate dalla protesta. È stato detto che l’Italia è disseminata di monumenti fascisti, il che rende scoraggiante affrontarli, o addirittura, che sono così “fusi” con il contesto da diventare quasi normalizzati, invisibili.9 D’altra parte, il dibattito pubblico esemplificato dai due articoli citati consolida la realtà del distacco dell’Italia di oggi dai suoi orrori passati. Dal punto di vista dei suoi difensori, ciò che Montanelli fece prima di diventare quello per cui è tuttora famoso, gli atti razzisti che ha commesso in un momento storico in cui erano socialmente accettabili, non dovrebbero offuscare l’opinione pubblica di lui. L’assorbimento di una parte del passato fascista italiano, come le infrastrutture e le eredità del welfare fascista da un lato, e la rimozione collettiva dei suoi orrori dall’altro, fanno parte della stessa rimozione del fascismo e della memoria coloniale dal discorso pubblico italiano. Come scritto dal primo studioso postcoloniale italiano, Angelo del Boca, il razzismo in Italia è “un prodotto della totale negazione delle atrocità coloniali, della mancanza di dibattito sul colonialismo e della sopravvivenza, nell’immaginario collettivo, di convinzioni e teorie di giustificazione “(Del Boca 2003, 34).

La mancanza di dibattito pubblico sul colonialismo italiano e sulla sua eredità si esprime continuamente nei sistemi di potere materiali e discorsivi che riproducono le gerarchie e i significati del patriarcato e della supremazia bianca in Italia. Inoltre, collega tali sistemi di potere a quella che Lombardi-Diop chiamava “la non razzialità dell’Italia postcoloniale” (Lombardi-Diop 2012, 176), secondo la quale gli italiani si vedono come “non marcati a livello razziale” e quindi raramente consapevoli del loro privilegio razziale di fronte a persone razzializzate. In questo contesto, la questione riguardante Montanelli e la sua statua è rivelatrice su più livelli. Pur mettendo in risalto l ‘”afasia coloniale”10 (Stoler 2011) della società italiana e la sua incapacità di ponderare adeguatamente il suo passato coloniale, sottolinea anche quanto la società italiana abbia incorporato l’eredità del colonialismo nelle sue strutture di potere contemporanee. D’altra parte, la rilevanza temporanea della protesta che si erge come un’isola di consapevolezza in un oceano di silenzi e negazioni rivela l’infertilità del dibattito pubblico italiano rispetto al suo passato e presente razzista. La storia di Montanelli e Fatima, sebbene esemplificativa degli assi intersezionali di oppressione del colonialismo e del suo retaggio contemporaneo, non può essere l’unico punto di discussione pubblica in una società che considera ancora il suo passato coloniale come marginale. Un dibattito più ampio, nel quale la storia coloniale italiana sia messa in primo piano nell’analisi degli assi intersezionali d’oppressione che tormentano ancora la società italiana, era ed è ancora molto necessaria.

Bibliografia

Ballhatchet, Kenneth. Race, Sex, and Class Under the Raj: Imperial Attitudes and Policies and Their Critics, 1793-1905. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1980.

Barrera, Giulia. “Colonial Affairs: Italian Men, Eritrean Women, and the Construction of Racial Hierarchies in Colonial Eritrea (1885-1941).” Ph.D. diss., Northwestern University (Evansville, Ill.), 2002.

Del Boca, Angelo. 2003. “The Myths, Suppressions, Denials, and Defaults of Italian Colonialism.” A Place in the Sun: Africa in Italian Colonial Culture from Post-Unification to the Present, edited by Patrizia Palumbo, 17-36. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Del Boca, Angelo. Italiani, brava gente?. Vicenza: Neri Pozza Editore, 2011.

Hyam, Robert. “Concubinage and the Colonial Service: The Crewe Circular (1909). The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 14(3), (1986): 170–186.

Lombardi-Diop, Cristina. 2012. “Postracial/Postcolonial Italy.” In Postcolonial Italy, edited by Cristina Lombardi-Diop and Caterina Romeo, 175-190. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

McKinley, Michelle A. “Illicit Intimacies: Virtuous Concubinage in Colonial Lima.” Journal of Family History 39, no. 3 (July 2014): 204–21.

Ming, Hanneke. “Barracks-Concubinage in the Indies, 1887-1920.” Indonesia, no. 35 (1983): 65-94

Sòrgoni, Barbara. Parole e corpi: antropologia, discorso giuridico e politiche sessuali interrazziali nella colonia Eritrea: 1890-1941. Napoli, Edizioni scientifiche Italiane, 1998.

Stoler, Ann Laura. Carnal Knowledge and Imperial Power: Race and the Intimate in Colonial Rule. (University of California Press, 2002), 44-45.

Stoler, Ann Laura. “Colonial Aphasia: Race and Disabled Histories in France.” In Public Culture 23, no. 1 (2011): 121-156.