by Andrea Tarchi, Euromix PhD Researcher, 1 July 2021

Overall, Italians don’t think much about the country’s colonial past. Any recent event that seems to indicate a correlation with former colonial practices, such as the current crisis of immigrants’ detention, is brushed off by the media as disconnected from a time long gone.1 In the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests that swept the world in 2020, an event changed this state of affairs, causing a rare media noise. It is June 2020, and several demonstrations in Milan, Italy, target the statue of famous journalist Indro Montanelli due to his involvement in a madamato relationship with an Eritrean minor during the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1936.2 Madamato was the colonial concubinage, or forced cohabitation practice, that involved Italian men and Eastern African women throughout the Italian presence in the region. Even if madamato is the most researched form of violent intimate encounter that characterized Italian colonialism, it was hardly known by the general public.3 In a rupture with the usual public disregard for issues related to Italian colonialism, the debate that followed the 2020 protests undeniably pointed the finger at madamato, with a considerable number of relevant newspapers and news websites explaining the practice to their readers.

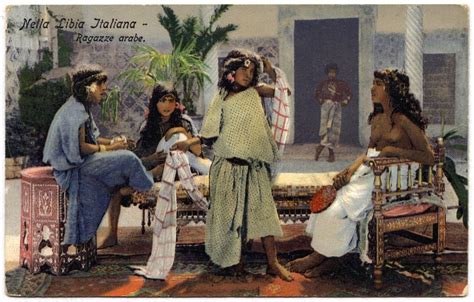

While this increase in attention is undoubtedly a positive outcome of the whole public debate on Montanelli and madamato, such focused rhetoric runs the risk of framing madamato as an exceptional practice specific to Italy’s colonial presence in Eastern Africa. This framing, in turn, risks hiding the fact that madamato was only one practical outcome of the pervasive patriarchal and racist structures of power that pervaded colonial Italy and that still influence Italian society. For this reason, in this blog, I want to talk about another less known and hardly researched form of racist, patriarchal sexual violence: the practice of mabruchismo or colonial concubinage imposed on Libyan women by Italian army officers. Even if less practiced than madamato, mabruchismo exemplified the racist, patriarchal structures of power that characterized Italy’s colonial power in Libya. Given the increasing notoriety of madamato provided by the media noise around Montanelli’s statue, it is more important than ever to add this sad page to the history of violence and oppression that characterized Italian colonial history.

Libyan Concubines for Italian Officers

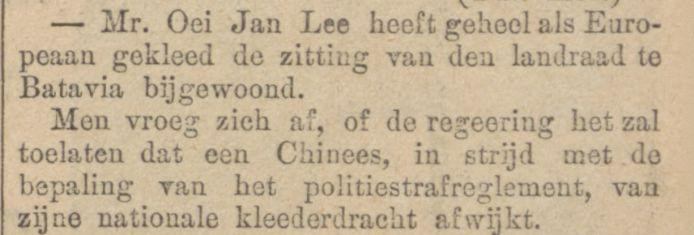

The term mabruchismo found its origin in the Arabic name Mabroukah, one of the most common first names given to Libyan women at the time. Its origin dates back to the beginning of Italian military presence in the Northern African territory in 1911. Although the Italian army’s military command had issued orders to respect the local population’s customs to sedate the fierce rebellion that welcomed Italian troops on their arrival, Italian officers started taking Libyan girls as concubines from the get-go. We see here the first contradiction that characterized Italy’s policies in the newly invaded colony. On the one hand, the army’s commander-in-chief Carlo Caneva wanted to convey rhetorical respect toward Libyan traditions by stating that “Libyan women are usually kept away from public life, and the indigenous are proudly jealous of them. Thus, everyone must abstain from any act towards them, which includes even looking at them.”4 On the other hand, however, the belief that “men, particularly soldiers, required an outlet for their (hetero)sexual energies and that the army must provide them with ‘safe’ sex”5 pushed the command to allow officers to take Libyan women as concubines. It is only 1916 when we find the first trace of mabruchismo in a circular order sent to the governor of Cyrenaica by an officer:

I have reason to believe that some officers who reside in the colony have hired indigenous women as concubines by either allowing them to live in their own house, or by settling them in a dwelling nearby, or by allowing them to still live with their families […]. The military discipline regulation deems unacceptable any form of concubinage. Such prohibition must be followed even more strictly in the colonial environment for obvious reasons regarding the officers’ dignity and decorum.6

Even if this order seems coherent with the Italians’ stance regarding the respect of Libyan women, it needs to be stressed that no officer was punished in Libya for taking women concubines before 1931. What was more pressing for the colonial administrators was not to enforce military discipline but to maintain the image of a colonizing power that was careful to the local traditions regarding the private sphere. Despite all the proclamations regarding respect of Muslim customs and Libyan women, the endorsement for mabruchismo continued through Fascism’s rise to power at least until the 1930s. The rhetoric and the policies of the first years of Fascist rule in Libya closely resembled previous liberal governments, with Italians portraying themselves as protectors of the Libyan population. Meanwhile, Fascism engaged in brutal military operations to repress the anti-colonial resistance. In the end, due to the military tactics of General Rodolfo Graziani, whose accomplishment would grant him the title of Vice-governor of the colony, coupled with heavy use of illegal toxic weapons, the resistance was wholly crushed.

The Prohibition of Mabruchismo in a Segregated Settler Colony

It is no coincidence that the first military punishments against mabruchismo happened only in 1931 when the colony’s militarisation slowly started to subside due to reaching the end of the repression of the Libyan resistance. The year 1932 would see the first waves of Libya’s mass demographic colonization, which entailed the deportation of Cyrenaicans who inhabited fertile lands to concentration camps and the arrival of many settlers.7 The new settler environment, coupled with Fascism’s turn to racist and segregationist ideology and policy in the 1930s, brought to an actual prohibition of mabruchismo. By 1931, we start to see Italian officers being reported to the colony’s military command for taking Libyan women as concubines:

A garrison commander in charge of a concentration camp for indigenous people found two officers engaged in romantic relationships with the concentration camp’s indigenous women.8

An officer, who was on duty in a concentration camp, fell into negotiations with an indigenous woman over the price to be paid for her daughter’s favors, acting therefore in a manner that was detrimental to an officer’s dignity.9

While on duty in a fort near a concentration camp under the Political Authority’s control, an officer started negotiating with a captive indigenous man the price to be paid for his daughter’s possession.10

It does not take long for Graziani, the Fascist military leader in the region and enforcer of Fascism’s segregationist policy in the new settler colony, to take action against a practice that is not admissible anymore. In this 1932 circular order intended as a response to the quoted reports, Graziani gives a complete picture of the regime’s new stance on mabruchismo:

I have repatriated four officers (one of them recently) because they made financial transactions (or anyway vigorously negotiated) to acquire indigenous women to keep them for themselves as concubines. This mabruchismo is one of the plagues that infested the colony. There are still some traces of it, or better still, some nostalgia; however, I intend to eradicate it.11

Graziani calls mabruchismo “one of the plagues that have infested the colony,” thus confirming that the repatriated officers were not the first to have concubines in the colony but only the first to be officially punished. Such development was due to the colony becoming a settler-colonial space, which entailed the need for the Fascist administrators to be less tolerant towards intimacies that crossed racial boundaries. Graziani played a role in the crackdown of both mabruchismo and madamato in Italian Eastern Africa.12 He was Fascism’s chosen man to end practices of interracial sex in the Italian colonies, where the racial purity of Italians was most at risk. The prohibition or tolerance of mabruchismo swayed according to the Italian administrations’ political plans and shifting ideologies, with a total disregard for local customs or Libyan women, no matter what the rhetoric toward them was.

Although not recordable through the voices of Libyan women absent from the archives, the exploitative character of mabruchismo is clear from the analyzed sources. We know from the sanctions to the officers that their parents sold some of them to the Italians, others must have been kidnapped, others again might have been former prostitutes or slaves looking for more economic security. We can assume that all these reasons, or a combination of those, might have brought them to leave their families much more than love or affection for the Italian officers that kept them as concubines, although that might have been possible as well. In the end, what is certain is that they were the recipient of colonial patriarchal violence by the Italian officers who bought them for sexual and domestic comfort while being used as political pawns by the various colonial administrations. Their exploitation was formally prohibited only when the Italian Fascist Party steered toward a racist and segregationist ideology, making interracial sex completely unacceptable in Italy and the empire.

Concluding Remarks

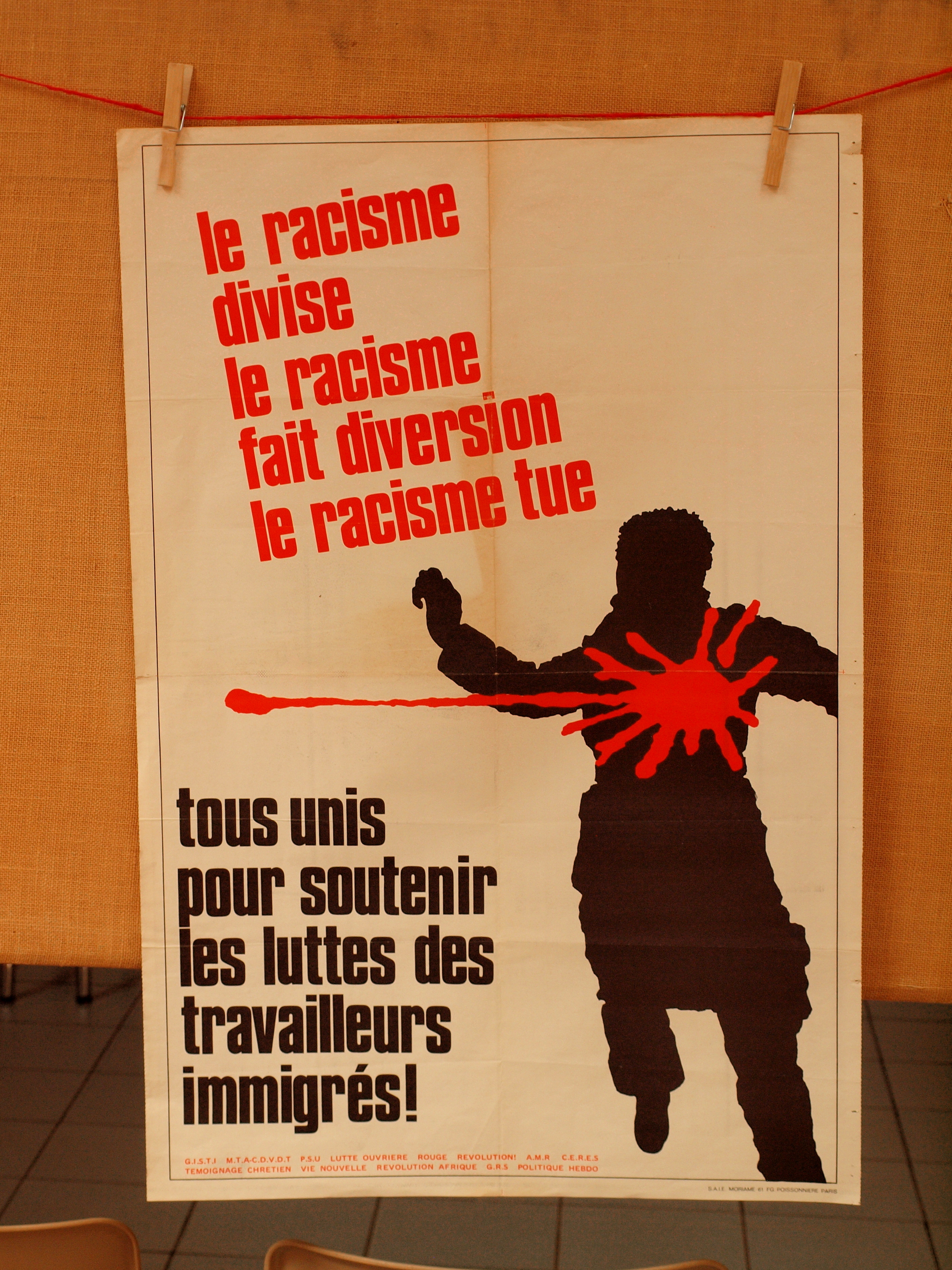

In response to the public debate over Montanelli’s statue and the memory of madamato, a journalist of the right-wing Italian newspaper Il primato nazionale wrote that “those condemning Montanelli alongside the custom of madamato, should praise at the same time the Fascist regime, as it put an end to this practice.”13 This reasoning highlights the ignorance that most Italian media and the public have on Italian colonial times. Mabruchismo and madamato were prohibited by the regime, not because of a sudden epiphany over their inherent violence. They were ended because the regime’s new ideological and material context could not allow these relationships any longer. In any case, the prohibition, tolerance, or even endorsement of these practices followed solely the colonizers’ political, ideological, and material needs, with a total disregard of the colonized women upon which they exerted their violence.

The public debate on Montanelli’s statue had the merit of highlighting the Italian public’s ignorance and hypocrisy over the country’s colonial past. By going over the less known and researched Libyan counterpart of madamato, this blog attempted to add a little more nuance and complexity to this ignored phase of Italian history. Before engaging in another fruitless and superficial debate over the memory of celebrities who engaged in colonial practices, it would be best for the Italian public to be aware of how even the darkest pages of Italy’s history created the country as it is today. The only way to do so is to put aside easy rhetoric and shallow debate to favor a nuanced analysis of the historical facts.

Bibliography

Barrera, G. 2004. ‘Sex, Citizenship and the State: The Construction of the Public and Private Spheres in Colonial Eritrea.’ In Gender, Family and Sexuality: The Private Sphere in Italy 1860-1945, edited by P. Wilson, 157-172. London, Palgrave Macmillan.

Bryder, L. 1998. ‘Sex, Race, and Colonialism: An Historiographical Review.’ The International History Review 20 (4): 806-822.

Campassi, G. 1987 ‘Il madamato in Africa Orientale. Relazioni tra italiani e indigene come forma di aggressione coloniale.’ Miscellanea di storia delle esplorazioni (12): 219-260.

Cresti, F. 2011. Non desiderare la terra d’altri: la colonizzazione italiana in Libia. Rome: Carocci Editore.

Del Boca, A. 2011. Italiani, brava gente?. Vicenza: Neri Pozza Editore.

Ponzanesi, S. 2012. ‘The Color of Love: Madamismo and Interracial Relationships in the Italian Colonies.’ Research in African Literatures 43 (2): 155-172.

Sòrgoni, B. 1998. Parole e corpi: antropologia, discorso giuridico e politiche sessuali interrazziali nella colonia Eritrea: 1890-1941. Naples: Edizioni scientifiche Italiane.